Fame arrives in mysterious ways. Nobody expects to go famous by giving a “UnCommon Core” lecture for the alumni week of the University of Chicago on June four through seven of 2015. But so it went for John J. Mearsheimer. Obviously, the man already enjoyed widespread recognition within his field. But his lecture and the fact that it was uploaded to YouTube as “Why is Ukraine the West's Fault? Featuring John Mearsheimer”. Mearsheimer might have drifted back in obscurity again if the Ukraine conflict had not escalated in 2022, but it did. His lecture is now Chicago’s most popular uploaded video by a factor of five. The second most popular video is another Mearscheimer lecture, and so are two others in the top five1.

The provocation thesis

John Mearsheimer’s central claim is that the West “provoked” Russia into attacking Ukraine by Expanding NATO into Eastern Europe. This meant that Russia found itself in a precarious situation in which it was increasingly surrounded by NATO allies who might jump to attack the Motherland at any opportune moment. Putin’s decision to fight back was predictable, rational, and forewarned.

The lecture did not go viral for some reason. Throughout all Ukrainian-Russian conflicts, the mainstream narrative has always staunchly blamed Putin for the whole ordeal, and people always look for the contrarian voice. That narrative also leaves a lot out, and John himself is a skilled orator and legitimate scholar. His thesis is not unique to him. For example, just on Substack it has recently been promoted by Andrew Doris, who is no slouch. Andrew is right to point out that too many people jump straight from noticing that Ukraine is righteous to concluding Russia wasn’t provoked without adequate justification.

Is it right

The difficulty I always had assessing Mearsheimer’s thesis (summerizeable as “The West provoked Russia”) is in parsing exactly what it’s claiming. Is it a moral claim? The usage of the word “fault” in the title seems to suggest so. But then again, he probably didn’t choose the title himself. I appreciate that Doris’ piece above clearly distinguishes the moral and the descriptive, and that it locates the thesis squarely in the descriptive. A clear statement of his thesis then would be “If not for NATO expansion, Putin would not feel the need to invade Ukraine, and the Ukraine war would not have happened” Summarized thusly, Mearsheimer and Doris are probably correct. If NATO really hadn’t moved one inch eastwards, Ukraine would now thoroughly be within Russia’s sphere of influence, like Belarus already is. There would be no reason to fight for it. What I don’t accept is the corollary, argued by both: that this means that NATO expansion shouldn’t have happened

Romania and Moldava as natural experiment.

Sometimes in history one nation is split up into two countries that each take distinct paths in history. North vs. South Korea, Canada vs the US, The Netherlands vs. Belgium. Cases like these are among the few times in history where you can actually hope to isolate the effects of historical forces on particular countries? Is Communism bad for your economy? To answer that question it doesn’t suffice to just compare the USSR to the USA. There are many factors that disadvantaged Russia regardless of their economic policies. Everyone in government is—and continues to be—extremely corrupt, the country is practically landlocked, and a large portion of the male population is alcoholic. These factors still keep Russia poor today, and things would be even worse if their vast territory didn’t give them access to immense mineral wealth. The many nations that have been split in twain between a communist and capitalist portion offer much more evidence on the track record of Communism. Germany, Korea, and China have each been divided in that manner, and in all three cases, the capitalist portion succeeded. It is no wonder that these countries come up time and again in defense of capitalist economics.

But see here another perfect natural experiment. Moldova and Romania really are one nation divided into two countries. They speak the same language, they used to form one kingdom, and there is an ongoing movement for reunification. Yet, a stark difference in their level of development since the Cold War’s end. Not only is Romania’s GDP per capita about twice as high as Moldova’s (almost trice PPP), Romanians can also expect to live 6 years longer than Moldovans do (75 vs 69 according to the world bank).

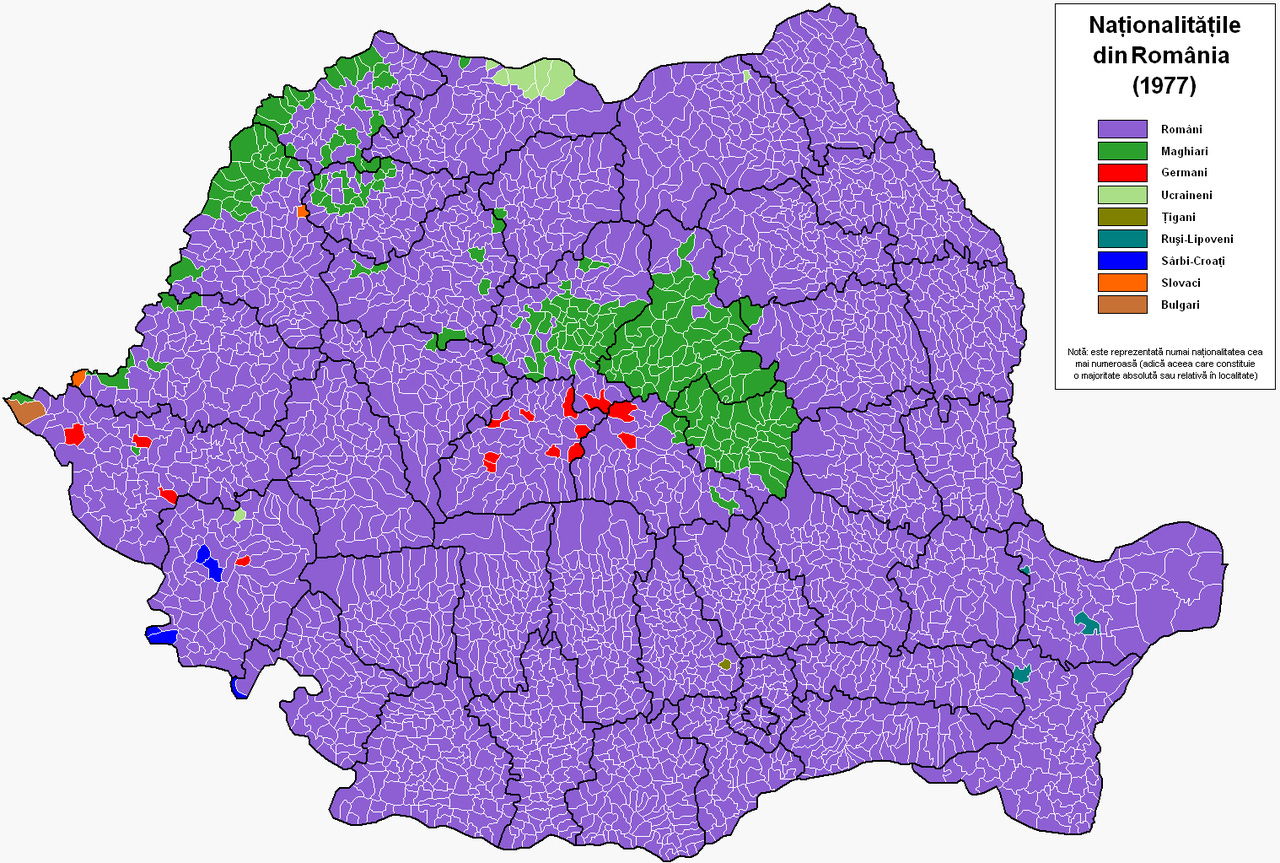

Moldova’s problems don’t stop there. A plurality Russian region in the west of their country has broken off and declared independence with the support of Russsia. Noticers may wonder if this had anything to do with NATO expansion. To them I will reveal that this has been going on since at least 1992, when among former Communist states, only East Germany had joined NATO. Transnistria is home to about one sixth of Moldova’s population, has a hammer and sickle on its flag and emblem, and boasts a GDP per capita figure that wouldn’t feel out of place among Sub-Saharan African countries ($2,584 if Wikipedia is to be trusted). Keeping a second region—Gagauzia—from declaring independence has been an ongoing struggle ever since. None of this has happened in Romania, and not for lack of majority-minority regions that could conceivably try.2

So what is the distinguishing factor here? You might suppose it could be that from the forties until the early nineties Moldova was part of the USSR, while Romania was governed by much superior(?) Romanian communism. I’m quite skeptical, because former adherence to the Soviet Union seems to have been no obstacle to the Baltic States. Quite simply: Romania is part of NATO, and it’s part of the EU. It benefits from access to the European market, EU development money, and the security that NATO provides. Moldova is not, and this effectively places it within the sphere of influence of Russia. These factors combined are enough to cut your GDP in half. You cannot make an honest assessment of whether NATO expansion was worth it without taking these benefits into account.

Doing the moral calculus

Imagine a world where NATO stays exactly as it was before 1990, the former Warsaw Pact countries are not folded into the western alliance, and they do not join the EU. Total population: ~100 million people. Going by the Romania-Moldova comparison each of them loses about about 5 years of life expectancy. But Moldova’s life expectancy happens to be low, even for non-NATO ex-Soviet states. But a dumb comparison of countries that did, or did not join NATO3 suggest an effect size no less than 4 years. This suggests that NATO expansion may have preserved a total number of 400 million life years.

This is only one of many benefits, but it is the most quantifiable, and it alone is enough to overwhelm the major cost of expansion: deaths in the War in Ukraine. Precise estimates in war are always difficult, and that are even more difficult while the war is ongoing. And in this case I’m just going of Wikipedia's estimates, but this only meant to give a sense of the order of magnitude here. Taking from those figures it looks like about 500 Russian civilians have died due to this war, along with 10-20k Ukrainian civilians. Ukrainian combatant deaths are much greater, perhaps 50-100k. So the total number of innocent deaths are about 60-120k.

As it turns out, the majority of deaths in the war are Russian(-alligned) combatants. Namely, somewehere between 150-250k. But I feel uneasy about straightforwardly including them in the total because doing so capitulates to a kind of moral blackmail I detest and refuse to capitulate to: “Submit to my will or I will kill my own people”. The more so becuase I do consider these soldiers morally blameworthy for participating in this war. The majority aren’t even conscripts! Neverthless, as a Christian I feel compelled to fall short of giving them no moral weight at all. So instead I will merely seperate out estimates that do and do not include the Russian soldiers. The one that does would come out to perhaps 200-400k people.

Suprisingly, a quick search suggests that the avarage age of combatants is not less than 40 years old, which is not dissimilar from the avarge age of a Ukrainian civilian. I therefore assume that they about 40 years of lifespan left in them. This means that the Ukraine war has cost about 2.5-5 million life years if you don’t include Russian combatants, 8-16 million if you do. Both of these figures pale in comparison to the life extensional effects above.

Of course the cost column doesn’t include all the other forms of suffering this war has inflicted, but nor did I include all the benefits. Both are probably proportional to the actual lives anyway.

Everything above is may look like utilitarianism summation to you, and you may not be a utilitarian. But even if you aren’t a utilitarian in the strict philosophical sense, surely you must agree that it is important to weight cost and benefits? No? Then what do you want to go for instead? Virtue ethics? I can do that! What is more virtuous; dying fighting for the liberty of your people, or dying early because you refuse to lift your sword against tyranny? I know my answer.

The alternatives

Until now I have simplified the possibility space to just two outcomes, yes or no expansion of NATO and the EU. But there are other possibilities.

For example: Most of the economic benefits of I rely my analysis on come exclusively from the EU, so why not fold Eastern Europe into the EU but nor NATO? This way you could have your cake and eat it too. All your economic growth without any of the American troops on the Russian border that make them mad. The EU even grants security guarantees to its members. But I doubt this works. Remember: Russia’s annexation of Crimea followed Ukraine’s then new intentions to join the EU, not NATO. Perhaps the Russian’s fealt that NATO would inevitably follow the EU, but why wouldn’t they feel this way in our counterfactual? More than that, I put a lot of credit in the call-it-idealism theory that the success of countries like Ukraine in itself threaten Putin’s regime and motivate his interventions.

All of that doesn’t even deal with how early the EU still was in its integration process when the wall fell. The EU wasn’t even the EU before the Maastricht Treaty of 1993, both in name and in essence. The European mutual defense clause only came into force in 2009, when the bulk of NATO expansion was already done. It is also no coincidence that EU membership has always followed NATO membership instead of vice versa. Ukraine would have been the first exception. A united European foreign policy is only now emerging, and without it it’s a fools errand to try wade into Russia’s would-be sphere of influence.

Maybe Eastern European countries could have formed their own defensive pact? I very much doubt that that would work. Poland would end up the heavyweight of that block, being about twice as populous as any other likely member of this block. It is both doubtful that other countries would be comfortable with that arrangement, and that it stands a change against Russia without western assistance, which would undermined the non-NATO nature of the pact.

Perhaps America should just ignore Eastern Europe and ally with Russia instead to counteract China. This last one happens to be Mearheimer’s perspective. And I for one don’t see what is to be gained from it. Perhaps you could deny China access to oil in case of some full-scale America-China war. But I—contra Noah Smith—don’t think that is a likely thing to happen.

More importantly, whatever benefit it could bring to the Americans, as a European I won’t stand for it, and I doubt most major European states would either. France, and Poland especially. It is their security that is in peril when Russia is allowed to play rough shot. In a deep dark past Mearsheimer predicted that Germany would resist NATO upon the end of the Cold War. That prediction might have come to fruition if America had taken his advice on Russia.

At best you could convince me that the Baltics were one step too far. Maybe.

The one non-Mearscheimer video in the top five is “"The New Jim Crow" - Author Michelle Alexander, George E. Kent Lecture 2013”. Quite a change of pace!

Thanks for the thoughtful reply. I have more respect for your broader thesis - NATO expansion significantly contributed to the deterioration of US-Russian relations and ensuing invasion of Ukraine, but that was worth it - than I do for the people who deny any connection between those things. And I think there were real benefits of NATO expansion for the countries that were able to slip under the umbrella in time.

But your specific argument here has too many rough assumptions to compel me. I get that you're not The Lancet, but it seems a real stretch to attribute a doubling of GDP and 4 years of life expectancy to NATO membership based on a naive comparison of countries in and out. Especially when you just admitted that even things like alcoholism rates and corruption levels play an important role. Is the causal theory there that investors just had more confidence investing, because they were less scared of Russian attack? You'd probably need some sort of regression controlling for many other factors. And as you said, EU membership/free trade has a more intuitive connection, while being less threatening to / exclusive with simultaneous Russian ties. You can argue one facilitated the other, but it's not a 1:1 relationship.

It's also not an all or nothing thing. There's a big difference between no NATO expansion after 1990 at all and NATO trying to expand all the way to Ukraine, as each subsequent expansion eroded Russia's buffer and increased Russia's perception of threat to its interests. If the US had expanded NATO to every single country now included BUT not declared that Ukraine would join in 2008, and publicly announced it did not support Ukraine's membership, that alone may have sufficed to prevent the invasion. Even if not, there were plenty of stopping points along the way that would greatly reduce your 100 million people/400 million life years figures.

Other commenters here have made other good points. But again, broadly speaking, I recognize there were benefits as well as costs and wish our policy had been driven more by conversations like this, that attempt a good-faith weighing of both sides of the ledger, instead of soaring feel-good rhetoric about the end of history and universal Democratic triumphalism.

Interesting article, I enjoyed it. I think you might be underestimating the risks and drawbacks associated with the Ukraine War. I tend to think that the greatest problem with great power war is not the immediate human cost, which is obviously awful, but the opportunity cost for global cooperation. The greatest threats to humanity in my view come from nuclear weapons, bioweapons, pandemics, climate change, and AI. And these issues can only be addressed internationally, due to collective action problems (and because these problems tend to transcend borders).

So when America gets into a cold war with other great powers, it's next to impossible to set up the global governance structures necessary to deal with these issues. For example, regulating biotech and virology labs will be even more difficult and more intrusive than IAEA inspections. I'm not optimistic about our chances to achieve global cooperation on these issues sans war, but it seems like it would be much easier if weren't at each others throats.