[By “balance of power” I mean the system where the government is devided into branches designed to keep each other in check]

In a country like the United States millions of people drive their cars to work every morning using the same roads at the same time. The only way to make that process even moderately save is if everyone agrees to drive on the same side of that road. Either everyone agrees to drive on the left side, or on the right. But which side is that going to be? There is no obvious reason to prefer one side over the other1. The only important part is that everyone drives on the same side. Every driver cannot join a zoom call each morning, zoom’s servers would collapse. What is needed is some sort of Schelling point. Luckily for the drivers there is one. We call this the law.

A good Schelling point/law needs to be a Nash equilibrium. That is to say nobody can have an incentive to break it. Or at least not enough people that the system of law breaks down. If you have that figured out you can start thinking about creating a system of law that actually produces good outcomes, but that is only a secondary considerations.

Most systems of law invest one person with the responsibility of the head of government. This presents a problem. Because this one person could single-handedly defect from the Schelling point. And if you haven’t designed your government in a careful manner he could land you in a completely different Nash equilibrium. In common parlance this is called a coup.

Traditionally there are two ways to deal with this reality. The first is autocracy, and was advocated for by Thomas Hobbes. In the system you solve the problem of aspiring dictators by giving up. Just give the head of state everything they want so that they don’t have any reason to coup, and deny everyone else the ability to coup. The advantage of this strategy is that it can be extremely stable. The disadvantage is that the best way to keep it so is to keep your population poor and oppressed. Compare North Korea—which has remained remarkably stable ever since the Korean War—to its southern counterpart—which “enjoyed” several coups in the same time-span. The choice of which is preferable is up to the reader

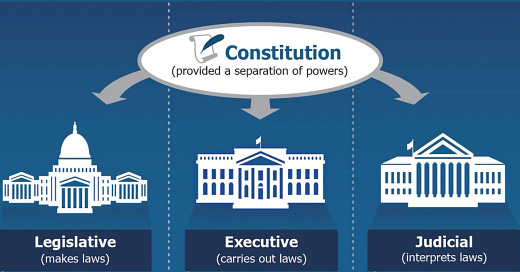

The solution second is constitutional government. Divide the power among several persons and/or institutions, and delicately design them so that no individual person or faction has the ability or incentive to coup. Its description alone demonstrates how hard this is.2

The United States of America came up with one solution. I give it an A for effort, I don’t think it works

The Holy Trinity

The logic behind three branches isn’t stupid. Three is a magic number of sort

Eén ei is geen ei.

To prevent a coup—so the founders thought—it is critical that no one faction complete controls the government. In retrospect this may seem overcautious. Several countries have made dominant-party democracy work without falling to tyranny (India, South Africa, Japan), but just as often the dominant party uses its position to entrench itself (Russia, Venezuela, Hungary). And even when it works out, single party dominance may let dumb ideas survive for too long. Perhaps India would have liberalized earlier, and South Africa wouldn’t have had load-shedding, if their politics hadn’t been dominated by the INC and ANC for so long. Creating one branch is no good.

Twee ei is een half ei.

If you create two branches instead the system doesn’t get much better, arguably it gets worse. Two factions vying for power? You don’t need to tell me how this ends! For the uninitiated: what you have just created is effectively a zero-sum game for power and with two players. There are no prizes for choosing the high road, so both parties is maximally incentivized to employ the most debauched strategy available to them. This might still work if you can rely on the voters to tell the honest from the corrupt. Experience has not shown to be a reliable strategy. Voters don’t pay that much attention to politics and don’t know enough about the structure of government to tell when someone is seriously breaking with norms. They can’t rely on media to tell them who is right either, because most media has a partisan bias that will exaggerate the norm breaking of the one party and obscure the norm breaking of the other. Never mind the biases and perverse interests of the voters themselves. Two is clearly not enough.

Drie ei is een paasei!

One and two not sufficing, Three is the minimum viable number of factions. Now whenever one of the factions threatens to amass to much power, the other two have the incentive to stop it. Whenever two factions fight the third can adjudicate in favor of the one that is behaving the most honestly. The voters can also rely on the third party to provide reliably on that same faction to relay them unbiased information (at least unbiased between faction one and two). This is why the constitution created threes branches, the legislative, executive, and the judicial branch.

The Truth Hurts

The problem should be quite obvious to any American reading this right now. The number of factions in the United States is not three, it’s two. It always has been two. And all the problems of two factions detailed above apply fully. There is no Executive, Legislative or Judicial faction. The idea seems ludicrous on its face. And the two-party system is not new. Save for a few negligible instances it has always been so. The first to vying factions emerged almost as soon as the constitution was enacted. The presidential election of 1792 might look peaceful from afar, with George Washington winning all available electoral votes. It was quite factional if you look under the hood. (Only the second election!)

Washington never wanted to be president. Everyone told him he had to. The nation would collapse into factionalism if he wasn’t there. He didn’t want to run for reelection either, but was promised all this partisan squabbling would be over before long, this promise was not kept. On his departure Washington made one last desperate plea to forego partisanship and faction. (in characteristically indirect, verbose 18th century language). If he had read (or alternatively remembered) Federalist #10 he might have realized the futility of his message. Maybe he did.

Whoever thought this was a good idea?

That is the logical question to ask. There is some English and French know-it-alls that apparently also thought separation of powers was a good idea. But let’s be honest here: All of these guys were just looking at England. England was the most “liberal” major country before the US. And it turns out that the government of England works was remarkably similar to the idea of how the three branches were supposed to work. And because England is so cool, so is their form of government.

England had at that time a reasonably strong king (executive), but he was not as strong as most of his colleagues throughout Europe. He was checked by a pretty strong parliament (legislature) and a court system that independently creates law through precedent (judiciary). The fact the the United Kingdom of today is completely dominated by one part of one branch (the House of Commons) is among history’s greatest ironies.

Contemporary observers were probably not completely wrong to see a connection between early modern England’s separation of powers and it’s relative liberty. But they were wrong in assuming that you could just apply it to a Republic like the United States and expect it to work the same way. The English system worked because the three branches genuinely were three different factions that were often at odds with each other. You had a king vs. parliament struggle, not a whigs-who-happen-to-control-the-kingship vs. tories who-happen-to-control-the-parliament struggle.

The difference here comes from the different ways in which offices get filled. The voter base that elects the president is fundamentally the same voter base that elect congress. It is anything but surprising that the president and congress often agree with each other. The judiciary doesn’t get elected, they get appointed by the aforementioned president and congress. They are arguably the most independent branch, which should surprise you given the content of the previous sentence. One supposes that lifetime tenure does have some meritorious effect. Nevertheless, the rulings of a be can be predicted with high accuracy based on the party affiliation of the president that nominated them.

Contrast the English system. The king gets his title by inheritance. A member of parliament his by election, and a judge by … the king (oops). Just the different ways they atain their position makes that their interest are probably not going to be aligned. If the Americans wanted to replicate that effect, they should have decorrelated the appointment mechanisms of the different branches. Which brings me to federalism. Unlike the separation of powers, I think federalism does work. The Federal government is elected by the American people as a whole. Any individual state government is elected by the people of that particular state. Even if the president an to governor of any particular state are of the same party, the demands of New Hampshire Democratic voters are different from national Democratic voters. A lot of liberty in American history was secured by the federal government checking the states and vice versa

America’s Constitution and its Consequences

It is hard for us moderns to imagine the conditions under which the framers (peace be upon them) were working when they designed the constitutional system. We are but fish swimming in the water of liberal constitutionalism. The constitutional framers invented the water. George Washington—for example—was the first president of the United States. But he was also the first president at all. The constitution choose that title for the republic’s head of state, and for that reason only “president” became the title for “a republic’s head of state”. The same way that the ancient Greeps had a recipe for how a polis works, we have a recipy now. And it is the American recipy.

Republics were almost unheard of when the constitution was composed. The primary example the founders drew on for historical parallels was the primordial Roman Republic. A foreboding parallel to draw one when most of your contemporaries are convinced that republics will fail when they grow to large. For contemporary examples larger than say a city they only had the declining Dutch and Venetian republics (which were feudal to boot). They were completely grasping in the dark. Given the limitations they were under, it is impressive that they managed to create a stable system at all. And not at all surprising that they failed to predict how their “seperation of powers” concept failed to work out.

But they grasped victoriously. Not only did their beat expectations, it became the template of how any constitution works. Even actual Autocracies pretend to implement a version of it. Russia has a “president”, a “supreme court” (but also seperate constitutional court) and bicameral legislature.

As the late Justice Scalia wants to point out, these “implementations” are usually only superficial. Dictatorships put rights in their constitution they have no intention to actually enforce, the upper house of legislatures is almost always mostly ceremonial, even in democracies where the lower house of the same isn’t. But those superficial implementations still dictate how we pretend the constitution works.

Going Dutch

In Dutch high school civics class I was thought that my constitution guarantees freedom of speech. In reality I have the freedom of speech to the extend that I follow the law3. To the extend I may have a ghost of constitutional right left, Article 120 of that same constitution robs me of it by stating:

The constitutionality of Acts of Parliament and treaties shall not be reviewed by the courts.

I was also thought that the Netherlands had separation of powers. I assert we do not. Our system is one of parliamentarian supremacy. All the other branches bow before the Staten Generaal. The parliament can do whatever it wants. If the executive doesn’t like it they must learn to like it. Resist parliaments mighty will and you will be fired by a simple majority vote. The judiciary has as little say in the manner. The legal system is based on civil law, not common law. A judge must always look towards instructions by parliament—not judicial precedent—on how to interpret laws. Think that a law is unconstitutional? Think again. Article 120. The constitution means whatever the parliament says it means.4

Yet our system has been working swimmingly ever since it was implemented in 1848. In my view this is because we have something better. Along the way it withstood the verzuiling. “Pillarization”, like polarization but four pillars not two poles. And “pillarization” was way more entranced than American Polarization is now. Imagine a world where the same work-floor was unionized under two separate Unions. One explicitly Democrat aligned, the other aligned to the GOP. This is how things worked in the Netherlands, only the unions were Catholic, Protestant, and Socialist (Liberals didn’t have a union for a confluence of reasons).

Nevertheless, Dutch elections of this era were basically boring, akin to censuses. Nobody even considered the idea that their political opponents might get rid of democracy. Adherents of both major American parties are convinced the the other will. This is a simple and obvious consequence of the number of parties that there are. The Catholic People’s Party gained 3%? Who cares! That’s like four seats in the lower house out of 150, they still need to work together with two or three of the other parties to do anything. Republicans gained 3%? THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY IS IN CRISES. THEY FUNDAMENTALLY LOST TOUCH WITH THE AMERICAN PEOPLE. SELF-FLAGELLATE AND CONTEMPLATE YOUR SINS.

Dutch elections don’t have nearly the stake American elections do. This is not only good for our mental well-being, but it is also more representative. Political opinion doesn’t swing that much between election cycles after all. And they organically mattered even less back when everyone was pilllarized and people stuck harder to their party.

All of this is achieved simply by adopting proportional representation. It turns out that it’s really hard to create a party that genuinely appeals to more than 50% percent of the voting public.5 American parties only get as high a proportion of voters as they do because the voters feel like they have not other choices besides the two. This is a natural consequence of a first-past-the-post mode of election. But how were the founders supposed to know? Democratic elections were unheard of in history as far as they could know about it.

Just now I explained how I don’t have freedom of speech. But now let me explain how I do. Imagine that someone comes up with a law that is against the freedom of speech. They bring it up for a vote. Everyone else notices what is happening and demands and explaination how it could be constitutional. The original proponent of the bill now has to explain how the law somehow is constitutional. You cannot openly support a unconstitutional law, because there are strong norms against it (enforced by shunning). The explanation fails and the bill strands.6 This very process has been plying out for years whenever Geert Wilders proposes something targeting Muslims. everyone points out that that violates freedom of religion. Wilders claims that Islam is not a religion but a “violent ideology” (as if those are mutually exclusive). Nobody buys it.

Unfortunately this is a fundamentally vibes-based mode of constitutional enforcement. There is a (judicial) Council of State that you can ask for advise about whether a bill would be constitutional or not, but their conclusions or not binding. This is how you can end up in a situation where was Mein Kampf is banned until 2017 and the selfsame Wilders gets convicted for hate speech. So while I’m 90% happy with the way things work right now, A little more judicial enforcement would be welcome.

In conclusion: Forget “checks and balances”, just implement proportional representation!

In practice roads in the US are designed with the assumption that everyone drives on the right, but pretend that isn’t so for the sake of argument.

For most of the history of western thought constitutionalism was considered practically synonymous to republicanism. If we still lived in that reality I would call these two forms of government “monarchy” and “republic”. Nowadays there are plenty of constitutional monarchies though. And so there are autocratic republics. I will stick to “autocracy” and “constitutionalism” for that reason.

The literal text of the relevant provision is:

No one shall require prior permission to publish thoughts or opinions through the press, without prejudice to the responsibility of every person under the law.

Despite how it reads, “without prejudice” is supposed to indicate an exception.

Formally, this is what the upper house is supposed to evaluate. In practice they vote as much based on policy as the lower house though.

South Africa’s ANC probably wouldn’t have been able to if they weren’t associated with the literal end of Apartheid. Similar considerations apply to the INC but they have the additional advantage of an FPTP voting system.

All throughout everyone pretends that the “without prejudice” exception doesn’t exist.

That's not what the word "coup" means. A coup is the overthrow of the current political system by actors exploiting power from outside that system (extralegal violence). It is not someone using their lawful powers under that system to produce unwanted outcomes.

Why is polarization necessarily bad and should be avoided? I don’t think freedom could be maintained in such a large and diverse country like the US without a significant degree of factionalism (you mentioned Federalist 10; could add 53 as well).

The Netherlands are ok because they have (not sure if that’ll be maintained) a high degree of cultural homogeneity (the norms that ensure freedom of speech with terrible constitutional protections). Once you get a country like Canada (even worse constitutional protections) that is diversifying rapidly and is more influenced by all things American like woke, MAGA, etc., you start to see liberties going down the drain.

Same with diverse countries (as in without many common norms) with proportional representation and weak constitutionalism like Israel. Goes to shit pretty quickly when everyone hates each other. :)